I grew up in a town stamped and molded by racial issues that were never discussed. On a few occasions, perspectives on race were danced around, touched on with incendiary language that, as a child, made me turn hot and fidgety. Sometimes the issues were visited with short and fiery bursts of opinions by people I loved and respected. In high school, a student’s confederate flag shirt set off a race riot, complete with classroom walk-outs and a local news crew stationed around our campus. I couldn’t tell you the details, however, because I didn’t pay much attention. I didn’t have to.

In our little town, racial divide was everywhere and stubbornly ignored at the same time. It seemed like we believed if we didn’t talk about it, racial division and discrimination didn’t exist. I certainly never acknowledged to my diverse friends in marching band what was happening around us, nor did they to me, and somewhere along the way I picked up the idea that to talk about race was too shameful, too fraught with danger.

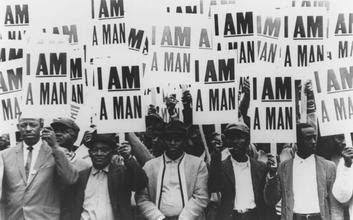

My senior year in college, I took a class called Civil Rights Rhetoric. Every Tuesday and Thursday, I sat with my mouth agape, intently listening to the details of Freedom Summer, the integration of Little Rock High School, voter registration and nonviolent protests. We watched grainy footage of speeches and read Martin Luther King’s, Letter from a Birmingham Jail. I couldn’t believe all of this had happened just 30 years prior and that no one had ever told me about it. I was a 21-year-old adult learning for the first time that there had even been a Civil Rights push in the 1960’s.

We were assigned a paper on the subject of our choice. I chose my hometown; I’d heard that my very own high school had been forced to integrate in the 70s after long resisting it. I wanted to know about it, so I began interviewing my neighbors and even the very judge who ruled for forced integration. As I prepared to interview him, my parents pointed out his house as we drove by. It was a house I’d passed thousands of times on the way to church, one that had always appeared shadowy, as if it wanted to hide, closed in by the self-protective bars on its windows. I wondered what had caused the judge to put those bars on his windows, but I didn’t have the courage to ask him when we sat for the interview.

When I spoke with adults I’d known all my life, and heard them talk about integration, it was strange. I’d never heard anyone talk so openly about it. All along, a question pounded in my head, how has this not been important to talk about? Why have I not heard these stories before?

I knew the answer. In their minds, it was “done.” Done like something we were embarrassed of and wanted to shove deep in a closet. Done like a closed book we never intend to open again. Done like it never happened or was buried so deep in history it had little bearing on the present.

After that class, I quit talking about race because my finished coursework seemed to take away my permission to speak and ask freely. Instead, I quietly read up on it, my interest insatiably piqued by what I learned in college.

Over the past few years, I’ve begun having those conversations again. They started when a black family visited our church, whom we invited over for dinner. After we finished our meal, the conversation turned toward their church decision. The wife asked, “Is it ok if we join your church?” She wasn’t asking for permission. She was referring to the color of their skin. In other words, “Will we be accepted? Will our children be valued and loved?” I was literally speechless, immediately racking my brain for something done or said that would have given them the impression they were unwelcome. And so began a conversation on race, church and the experiences they’d had in their professions, past churches and with their children. Their openness and honesty gave us permission to ask anything but, even more so, their answers challenged my perspectives and perceptions about race in America.

They joined our church and we’ve grown as friends. Conversations with them over the years have taught me how much I still don’t know. They’ve taught me to be a forever learner.

But, primarily, they’ve taught me that race is not only ok to talk about, it’s something we need to talk about it.

It took me decades, but struck me recently that—as much as we (rightly) love our country—it was founded upon institutional sin. The basis of our country’s economic success was slavery. We (“we” meaning white folks) don’t like to think about that. We don’t like to look at our country’s sin so directly. We don’t like to think there could be generational consequences for it.

As a Christian, however, I believe that we can, and should, take a good look at our sin because Christ has made a way to cleanse us from it. We don’t have to be afraid to acknowledge slavery, lynching, Jim Crow laws and the existence of racial injustice. To do so isn’t to denigrate law enforcement officers—people doing a tireless, thankless job who deserve our respect—or to choose sides according to skin color. As a human race, we are a people who mistrust others different from ourselves. We must acknowledge our apathy and indifference to the experience of others. If we desire unity and harmony in our nation, we should not to wait for the “other side” to agree with our perspectives and ideas, but confess and repent before Jesus. We must acknowledge our nation’s sin, weep over it, grieve over what it has done and confess it before God and one another. Jesus’ gospel teaches us that confession and repentance lead to forgiveness and reconciliation—first between God and man and then between men.

What is happening in our country isn’t about police officers vs. the black community. We don’t have to choose sides. What is happening in our country is what happened for me during a Civil Rights class and during the dinner with our friends. These events open conversations we too often resist or don’t know we need to have. There is opportunity springing out of the blood and tears of our neighbors. The question for each of us—especially for Christians, who have been given the ministry of reconciliation by Jesus Himself— is simply, “will we have these conversations?”

Are we willing to engage with people who are different than us? Are we willing to ask questions of real people and listen to them? Are we willing to love our neighbor by first seeking to understand them? Are we willing to love our neighbor by reaching out first?

It seems the wound we hoped had healed never actually did. The black community has been trying to say this for a very long time. Perhaps everyone is now ready to listen. So, now what? We must do what the wounded do—examine it, clean out the impurities and address it in a way that brings true healing. The only way toward the unity we desire is through the powerful love of Jesus, made tangible as we seek to serve one another, not kill and blame one another.

If you want to read more to gain understanding about the racial divide in our nation, I suggest these resources:

- The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson

- United: Captured by God’s Vision for Diversity by Trillia Newbell

- Parting the Waters: America in the King Years by Taylor Branch

This post originally posted here.

Published August 22, 2016